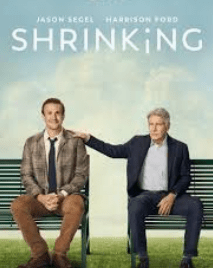

Apple TV’s show Shrinking debuted its third season recently, and I hopped on that narrative train, watching the first two half-hour episodes. I liked this show when I stumbled on it last year, for its humor, but mainly because of its completely not-Oregon-winter vibe. People in a beautifully photographed upscale part of somewhere California. Sunny skies, backyard swimming pools, perfect yards. And there’s the unlikely office setting for the three protagonists: psychologists all.

Not grim or dark, thank God. Before that I’d been watching Slow Horses whose grim darkness is only slightly elevated by the outlandishness of its grimmest darkest character. Shrinking was conceived and built by the same folks who brought us Ted Lasso, whose continued underlying theme — wrapped in great humor — is forgiveness. That’s not something Hollywood usually builds serial videos around. Shrinking is in that vein, but different.

After watching, I found myself both drawn in yet also popped out of the story. I wondered what the critics were saying about it. They were saying a lot. Some found it too sweet, a soft and soapy confection. Others found the underlying narrative — the importance of connected, supportive friends — touching and important. And several mentioned the foul language liberally used throughout.

In the current state of the world, I will take a confection where I find it. Human sweetness, friends and neighbors helping as best as their imperfect selves can, I’ll have a helping of that, please.

To single out one of those sweet moments: A gay couple who are adopting a single woman’s infant in what appears to be an open-adoption process, decide unequivocally that they want to change their minds, close the door on contact with her after the baby is born. But then in the interaction with her where they plan to tell her this, they can’t bring themselves to do it. Because of who she is, the way she is. Because of who they are, the way they are. This little side story touched me. It’s how we make decisions in real life: announcing to ourselves that we absolutely will not do this or that thing only to shift gears midway.

Because I am not a huge fan of the actor playing the protagonist, some of his scenes pop me out of the story. I’m no longer embedded in it. I’m just sitting there wondering if they could have found a more charismatic actor to play that part. But somehow, some way, the what-will-happen-next-ness of good storytelling pulls me back inside this fiction and when I come out at the end, I am uplifted.

For people who don’t like seriously foul language, I don’t recommend this series. Nothing can shoot a person out of the joy of story immersion faster than language that deeply offends.